Written by: Lourdes Mederos, UF/IFAS

Florida’s coastline may one day host more than oysters, clams, fish and shrimp. Researchers at the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) and Florida Sea Grant are asking whether seaweed could be the state’s next big sustainable crop.

The effort, launched last year with a $250,000 grant from NOAA’s National Sea Grant Aquaculture Program, brings together scientists, industry partners and Extension agents to answer whether seaweed is a good fit for Florida. The findings could pave the way for a thriving seaweed farming industry much like it serves as a high-value crop in regions in Europe and the Americas.

Led by Ashley Smyth, an associate professor of soil, water and ecosystem sciences at the UF/IFAS Tropical Research and Education Center, the project team shared updates recently that sparked strong interest from researchers, aquaculture professionals and entrepreneurs in exploring the feasibility and economic potential of seaweed farming in Florida.

“Seaweed aquaculture has tripled over the past two decades — with Asia producing nearly all the supply — and it’s one of the fastest-growing commodity sectors globally,” said Angela Collins, Florida Sea Grant assistant Extension scientist specializing in marine fisheries and shellfish aquaculture at the UF/IFAS Tropical Aquaculture Lab and a co-principal investigator on the project.

Smyth explained that the research focuses on the potential and the practical limits of cultivating seaweed in Florida’s warm waters.

Gabrielle Foursa identifying a site to collect data while snorkeling in Tampa Bay. Credit: Angela Collins, UF/IFAS

“Seaweed acts like a sponge, pulling excess nitrogen out of the water,” she said. “If harvested, it removes that nitrogen completely, which means it could serve as both a product for growers and a tool for improving water quality.”

Florida’s unique environment presents opportunities and unknowns.

Seaweed is prized not just for food in other parts of the world.

“A lot of times people think immediately of food when it comes to seaweed farming, but it’s also used in pharmaceuticals and nutraceuticals, as well as thickeners and bio packaging, fertilizer and animal feed,” said Collins.

On the global scale, seaweed aquaculture has also been recognized for the ecosystem services it may provide, and it’s been celebrated in several regions for its benefits for water quality.

Right now, seaweed farming in Florida exists at a small scale and only in enclosed tank systems. Before farming can expand into coastal waters, researchers must identify which species naturally occur in Florida’s waters, evaluate their ability to absorb nutrients, test cultivation methods and analyze whether the economics make sense for producers.

On the team is doctoral student Gabrielle Foursa who is leading much of the hands-on work, cataloging species and beginning growth trials.

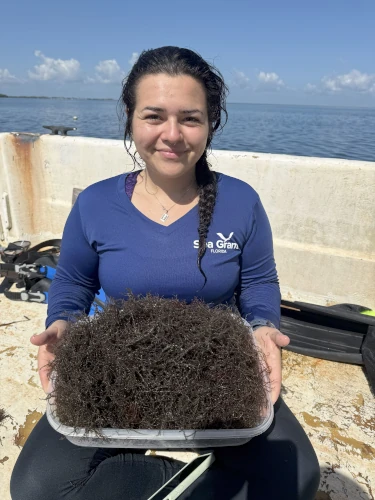

Gabrielle Foursa holds seaweed retrieved from a sampling site in Tampa Bay over the summer. The predominant species of seaweed seen in this August sampling is scientifically called Acanthophora spicifera. Credit: Angela Collins, UF/IFAS

“Step one is really understanding what we have here in Florida waters,” said Foursa. “From there, we can start to figure out which species might be useful, and for what purposes.”

That usefulness could extend into compounds that are already in everyday products.

Contributing to the project as a co-principal investigator is Dail Laughinghouse, associate professor of applied phycology at the UF/IFAS Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center, with expertise in algae biology and cultivation.

“Seaweed compounds already show up in everyday products, from ice cream and salad dressings to toothpaste, and different species may hold untapped potential for health and sustainability,” he said. “Knowing which native species, we have is the foundation for exploring those opportunities.”

Beyond these everyday uses, Laughinghouse emphasized that algae could hold an even greater promise for the future.

“Different species produce different compounds — from heart-healthy omega oils to natural pigments with anti-inflammatory or anti-cancer properties,” he said. “That’s why understanding which native Florida seaweeds we have is so exciting. We don’t yet know what they’re capable of, but the potential is enormous.”

The team is also assessing potential markets with input from UF/IFAS economist Andrew Ropicki and collaborating with shellfish grower and industry partner Aaron Welch of Two Docks Shellfish Co., who has already piloted several small-scale trials on Florida’s Gulf Coast.

A look at macroalgae specimens from the project’s first collection event in spring before being sorted. The project aims to identify which species are in the area and in what abundance. Credit: Gabrielle Foursa, UF/IFAS

“Florida’s vibrant shellfish aquaculture and commercial wild-caught seafood industries make it an opportune place to explore seaweed farming, since existing fisheries operations provide a capable workforce and functional working waterfront infrastructure,” said Collins.

Ropicki is evaluating which product markets Florida seaweed could serve and whether cultivation makes financial sense.

“The key is finding opportunities where local seaweed offers unique value, whether through niche markets or environmental benefits,” he said. “Our goal is to understand not just if seaweed can grow here, but if it can make financial sense for growers,” Ropicki said. “Florida farmers face higher costs than producers overseas, so we’re looking for opportunities where local seaweed could serve niche or high-value markets or even provide environmental benefits that add economic value.”

The team emphasized that this is still an early-stage project.

“This is about managing expectations,” Smyth said. “The answer might be ‘yes.’ that seaweed aquaculture could thrive here. But if the answer is ‘not right now,’ that’s still a win because it saves growers time, money, and effort, and helps us target where future investments should go.”

The post Is seaweed aquaculture the next big crop for Florida?, written by Lourdes Mederos, first appeared in the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences’ Agriculture blog.

The mission of the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) is to develop knowledge relevant to agricultural, human and natural resources and to make that knowledge available to sustain and enhance the quality of human life. With more than a dozen research facilities, 67 county Extension offices, and award-winning students and faculty in the UF College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, UF/IFAS brings science-based solutions to the state’s agricultural and natural resources industries, and all Florida residents.

Florida Sea Grant is one of 34 Sea Grant programs supported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in coastal and Great Lakes states that encourage the wise stewardship of our marine resources through research, education, outreach, and technology transfer. The program is hosted at the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS). In addition to NOAA and UF/IFAS, the program is a partnership between Florida universities and county governments.